9. Drought buster – Common Stork’s bill.

2 September 2025

11. Antipodean alien in the lawn.

4 November 2025What a difference a bit of rain can make. Above is a local lawn in summer drought, and then after a month of much more usual and showery autumn weather. The dark green patch in the lawn in drought is a patch of yarrow. It still shows as darker green in the rain-watered lawn.

Another stalwart in drought-hit lawns throughout this past spring and summer has been yarrow. As an English common name, we simply call it “Yarrow,” though goodness knows why. It is not a usefully descriptive name like “Mouse-ear chickweed,” and although it does share three consonants, I remain mystified with the explanation in the etymology books that it comes from the word “gear we” — the old English name for yarrow. I think I prefer modern English.

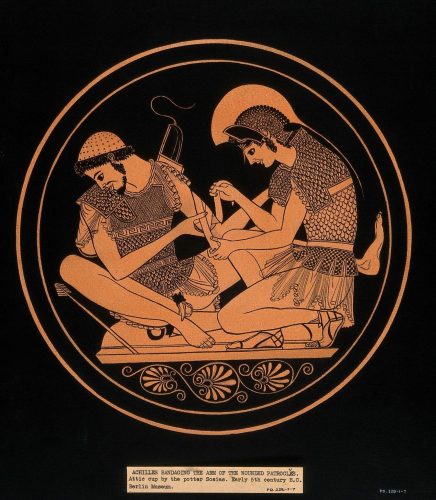

Its proper botanical Latin binomial name is Achillea millefolium, meaning Achilles’ thousand-leaved plant. What has it got to do with Achilles, and does it have a thousand leaves, you might ask?

The ancient Greek hero, Achilles and his Troy-invading compatriots, are said to have used it as a pain-relieving and blood-staunching battlefield medicinal herb. In one version of the ancient myths, it was the critical ingredient of a protective magical brew his mother dipped him into while holding him by his heel as a baby, while most other authors say it was the mythical river Styx she dipped him into.

It is mostly mythological, so is of little practical consequence. But you cannot say plant names are always dull, they can be full of history, myth, and magic. Linnaeus, the great namer of plants, used the story as inspiration in his binomial plant naming frenzy some 272 years ago, naming the entire genus after Achilles.

Whatever Achilles, his compatriots, or his mother were up to, the “thousand leaves” species name refers to the feathery nature of the yarrow leaf, and is one of the features that has given yarrow its notable drought tolerance.

I want to rave about this plant. I really do, but I shall hold myself in check. It has amazing physiological adaptations that allow for its survival in challenging environmental conditions. Its ongoing survival throughout this year’s double-drought are clear evidence of that. This plant has a future in drought-resilient lawns, for sure.

The leaves are the part of the plant we see most, and are directly relevant to the optics of a lawn, so I’ll restrict myself, and focus on them.

Achillea millefolium in the lawn. Yarrow has a characteristic known as plasticity of form. Here it is growing in a mown lawn where it is not much taller than the pound coin I added for reference. It can change its form in response to environmental influences such as mowing by remaining low growing in lawns. As shown, it can produce flowers even in its height-reduced state. In garden borders without the influence of the mower it can grow to over a metre tall.

Just in case you happen to be wondering, and as curious lawn aficionados I am sure you are; the primary advantages of yarrow’s feathery leaves are:

- An increase in the total leaf surface area. A larger leaf surface can increase the opportunity for photosynthesis, and therefore growth.

- The small size and the arrangement of curling lobes in finely divided leaves can help reduce transpiration rates. This is beneficial in conserving water.

- Smaller, but more numerous stomata, enabling tighter control over water loss during dry conditions.

- Excellent gas exchange, since air moves between the many leaflets allowing free absorption of CO₂ and releasing oxygen better than in most whole leaves, especially in crowded vegetation.

- Light Penetration: In dense vegetation, finely divided leaves can allow some light to penetrate deeper, ensuring lower leaves still receive sunlight for photosynthesis even when the canopy is thick.

- Cooling Effect: The increased surface area can enhance evaporative cooling, helping to maintain leaf temperature and reduce water stress during high heat.

- Flexibility and Strength: Fine divisions can enhance the structural integrity of leaves, making them less prone to complete damage from environmental stressors like wind, extreme temperatures, and footfall.

They also can look attractive, and can be pleasant to touch.

In the case of yarrow, its leaves and other parts of the plant also come with a distinctive scent, often described as a mixture of chamomile and pine, or somewhat chrysanthemum-like. Which leads to the next drought-resistance feature of yarrow leaves, its trichomes (plant hairs).

Plants do not have hairs, only animals do, but plants have something that can sometimes look rather like animal hairs. These are known as trichomes. There are many types, and include ones that have chemical /scented oily secretions that are the source of many essential plant oils. These are known as glandular trichomes and are quite unlike animal hairs.

If you look at the image and notice the sunken glandular trichomes, you will see how unlike hairs they can be. They have some useful advantages if you are a plant, they assist in:

- Water Conservation. Trichomes can reduce transpiration by creating a boundary layer, thus minimizing water loss in dry conditions.

- Defence against herbivores. They can deter herbivores by secreting repellent oils and metabolites (the scent).

- Sunlight protection. Trichomes can help filter and shield the plant from excessive UV radiation, reducing damage from intense sunlight.

- Condensation of moisture. They can capture dew or humidity.

- Evaporative cooling. Trichome oils may evaporate and lower leaf temperature.

There are also micro-ridges along the leaf. These help enhance water retention and reduce water loss by creating a texture that can trap moisture between the ridges. They also assist in the absorption of light and improve photosynthetic efficiency. Another bonus is that the subsequent rippled texture is difficult for leaf-munching insects to get good footing on, and the same applies to pathogens, that struggle to adhere to the leaf surface.

Along with glandular trichomes, yarrow also has secretory ducts within most parts of the plant including the leaves that synthesize essential oils, and contribute to the plant's aromatic properties and chemical defences.

I am still tempted to waffle on extensively about this amazing lawn plant, but will finish up on noting that the native form is usually white-flowered, but has naturally pink forms too. I spotted a notably pink wild-form, and just as I came to photograph it, a bumblebee joined me. That says more than I could about the flowers!