10. Achilles’ thousand-leaved plant.

15 October 2025

12. A lawn, or perhaps not?

12 December 2025Time for another lawn alien.

Like my previous Lobelia example, this one also hails from the far side of the planet. Not Australia this time, rather its nearby temperate-climate neighbour (and one of my favourite places in the whole world), New Zealand.

New Zealand has many unique plant and animal species, and although this plant genus can be found elsewhere in the Southern Hemisphere, its stronghold is undoubtedly in New Zealand.

Specifically, Leptinella dioica is the plant I am writing about today. Never heard of it? You might know it under another name!

Read on…

Not known during Linnaeus’s C17th naming frenzy, and first named by French botanist Henri Gabriel de Cassini in 1822, it was later fully described by British botanist Alexandre Joseph Dalton Hooker in 1852. The Leptinella were understandably, but also confusingly, initially placed into the genus Cotula, before Leptinella was fully reinstated as a separate genus in 1987.

Alas, much of commercial horticulture is yet to fully embrace the name reversion that happened nearly 40 years ago, and sells the genus under both its previous and current names.

The name “Leptinella” is derived from the Greek word “leptos,” meaning “slender” or “thin,” combined with the Latin suffix “-ella,” which is often used to denote small form. It is a sort of hybrid Greek-Latin plant name, but not quite as interesting as naming a plant after the tale of medical and magic potions, leaf form, and an ancient Greek hero, as in my previous post. I wondered what Linnaeus might have named it?

With that in mind, I decided to sidetrack and ask an AI what Linnaeus might have come up with as a descriptive name. The AI suggested that Linnaeus might have described the plant in Latin, something like:

“Habitat in Novae Zelandiae litoribus. Planta humilis, dioica, foliis pinnatis; capitulis minimis discoideis”

(“On the shores of New Zealand. A humble, dioecious plant with pinnate leaves and very small discoid heads.”).

Making it clear just how much simpler a binomial naming system is; but what I really wanted was a Linnean-inspired binomial name. I focussed the AI to the task.

The AI confidently lied a bit, as is usual, tried to appear smart, also usual, but after a bit of correction and some relevant prompting, a hypothetical binomial name was achieved.

In a manner similar to the naming of Achillea millefolium by Linnaeus, and based on using Māori mythology, a plant characteristic, useful botanical Latin, and the additional fantasy that Linnaeus himself might contemplate the name, my final selection for a binomial Linnaean-inspired name is “Rongia dioica.” Rongo is the Māori god of cultivation. It seems an appropriate choice, although Rongia maritima was a close second. The AI preferred another name.

Intrigued? To find out why I made that choice, the transcript of our little plant naming chit-chat, and how AI and I came up with the name can be found HERE.

The actual species name “dioica” is botanical Latin, and refers to types of plants that have separate male and female individuals. This is relevant, since excepting a particular and rare subspecies, a Leptinella dioica plant should be either be male or female, and both forms are required for successful seed production.

It means if you just use one garden centre sourced plant to get started in your lawn, it is unlikely to produce viable seed. Determining whether the plant is male or female is tricky without a magnifying lens, so it is best to not worry about seed production, and just let the plant spread vegetatively. Most garden centre plants will have been produced by vegetative cuttings from a single source mother (or father) plant, so there is no guarantee you would pick up both sexes anyway.

All Leptinella are Southern Hemisphere plants, and mostly occur in New Zealand. They are part of the worldwide daisy family — the Asteraceae. There are thought to be 34 different Leptinella species and 13 forms of L. dioica. Apart from the obvious size and habit difference, some Leptinella have passing similarities to Northern Hemisphere Achillea (yarrow); although yarrow, like the majority of the Asteraceae family, is monoecious, with both male and female parts within the same flower.

Unlike Achillea, Leptinella flower heads are singular, very small, and usually a rather dull greenish-yellow colour; they are notably underwhelming from a gardener’s perspective. In the UK, it tends to be the smaller and under-appreciated ground-dwelling insects and small flies that pollinate them.

Members of the genus are unsurprisingly not grown for their tiny, hardly-noticeable flowers, whereas some bright yellow, button-flowered Cotula (that genus they were first put in), are. It is why an irrelevant common name for Leptinella is still sometimes listed as “Brass buttons.” It is a hangover from being previously placed in with Cotula, a genus that itself continues to have “Brass Buttons” as understandable common names.

It is a mat-forming, hardy perennial, with shallow, creeping rhizomes and relatively small, divided, fern-like green leaves that may bronze up a bit if in full sun. This plant typically hugs the ground, rarely reaching more than 2cm in height, and in time a single plant and can spread to a meter or more.

If grown as a single species, it can form a dense ground cover that shades the soil beneath it and may exclude other plants from establishing. It is a coastal plant in its native habitat and tolerates moist and seasonally wet soils. It also appears to tolerate drought conditions similarly to coastal yarrow.

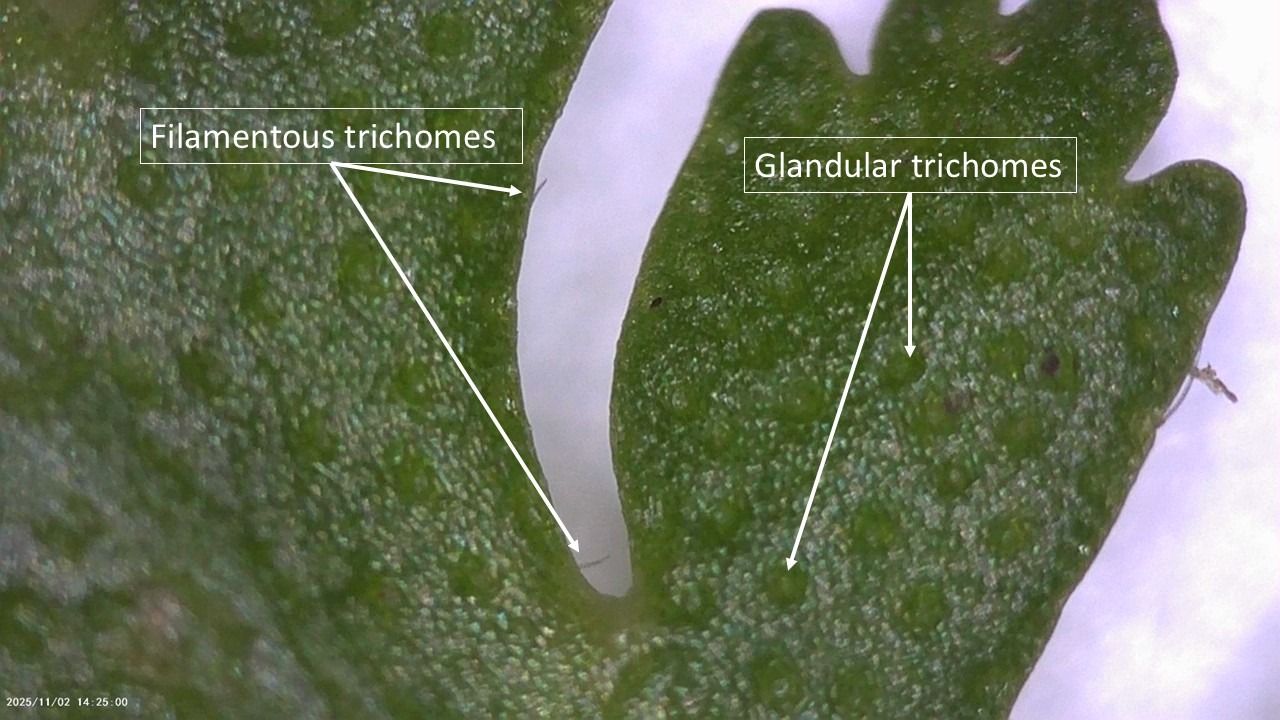

In the double drought of 2025, it ceased growing, but remained green throughout the spring and summer, especially so in partially shaded locations. It also notably appeared to influence soil moisture retention beneath its spreading-mat form, with its slightly succulent leaves closely covering and shading the soil. Its small succulent leaves, extensive rhizomes and glandular trichomes appear to have given it more drought tolerance than is generally associated with it. Though, I also wonder if this tolerance might be partially through bioengineering the immediate environment by keeping it moisture retentive.

Its surface covering characteristic is a double-edged sword, perhaps? The Leptinella is becoming a dominant species in the pictured lawn, but at the same time it is helping in maintaining soil moisture.

It (and other Leptinella) is used in some parts of New Zealand in the making of bowling greens, with a big plus point of hardly ever needing to be mown. The two local park bowling greens hereabouts suffered with this year’s drought and required watering. I shudder at watering any lawn in a drought.

It makes me wonder, that if droughts are to become more frequent and more intense, and folk wish to continue to play lawn bowls, then perhaps it is time to sod regulations (pun intended), and to try a Leptinella bowling green here in the UK. I did mention this to those playing on, and those managing, the local bowling lawns; apart from one savvy individual, the look of horror at the thought reminded me of the looks and comments I received when I first postulated the idea of a lawn without grass.

We shall see...