5. Dry lawns

23 May 2025

7. Aliens in the lawn.

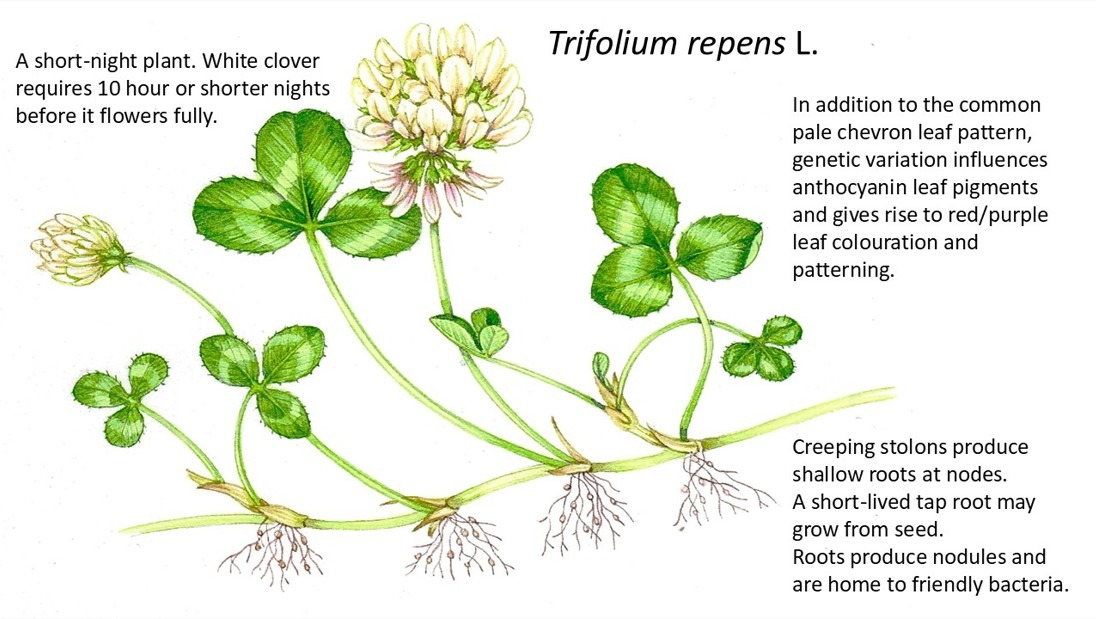

9 August 2025June is nearly over and of late I have noticed posts on various social media platforms on the topic of clover lawns. Trifolium repens (white clover) in particular.

In these years of rapidly declining insect numbers, it is more noticeable now when we see clusters of pollinators in one spot, be it butterflies or bees.

Dozens of bees foraging on lawn clovers may have been entirely unremarkable 30 years ago, but are noticeable today. Sadly, not especially so for those younger people who have grown up in the nature-depleted world we currently inhabit.

My younger students do not notice the tens of millions of missing Elm trees; they have never known them; and a dozen butterflies on a Buddleja butterfly bush is more often than not a notable event, and therefore a great selfie opportunity. The days of seeing just how many different types of butterflies you could get in a jam jar are alas seemingly becoming a thing of the past.

Bees like clovers, especially white clover. It is the right colour (bees are especially attracted to white, purple and violet), and is an important accessible food resource after the June gap which can sometimes see continental and British bees die from starvation between seasons. It has been noted that adding white clover to lawns can be helpful in supporting all kinds of bees, particularly small-tongued pollinators such as honey bees. In urban lawns, dandelions in spring and white clover in summer can literally be lifelines for bees.

The buzz of pollinating bees anywhere is seen by most as a good thing, but not entirely, as some folk are concerned that bees visiting lawn clovers may sting if accidentally provoked, and some people can react very badly to stings. Clover can stain clothing and clearly shows the chemical damage caused by pet urine. It is rarely possible for a clear win it seems.

Clover lawns have been around for quite some time, although for the most part the clover is simply a constituent of grass-based lawns rather than clover-only lawns.

Including it in proportions of around 5 to 10% in grass seed has been how our predecessors would ‘green-up’ their lawns. The richer and deeper green of clover leaves adding to, mixing with, and improving the overall green of the lawn. It is not primarily the effect of root nodule produced nitrogen fertiliser, as is sometimes claimed.

Clover family plants (Leguminosae) make relationships with specialist soil bacteria (Rhizobium leguminosarum) that are encouraged by the plant to live in their roots. Together they form nodules the bacteria can inhabit. The clover plants go on to exchange carbohydrates (sugars) from their own light-powered photosynthesis for nitrogen extracted from the air by the bacteria. It is a mutually beneficial relationship.

The relationship is usually a mostly closed system exclusive to the host clover and its bacterial guests, although a small amount of nitrogen may leak out of the system and be used by other microorganisms nearby.

The largest nitrogen leaks, although still quite small, tend to occur when the clover plant is stressed, notably when it is eaten or mown.

Grazed or mown plants may reduce the size of their roots in response to the sudden defoliation, since they subsequently no-longer have sufficient leaf area to support and maintain them with carbohydrate anymore. With fewer roots, the root-dwelling bacteria can become effectively homeless and the nitrogen they have produced is no longer connected to the plant and becomes briefly available in the soil. It is swiftly scavenged by other soil dwelling organisms, most particularly by other microorganisms.

The direct influence of this released nitrogen on neighbouring plants as a fertiliser is rather limited, and is usually somewhere between 4% to 14% of all the available clover nodule nitrogen; the soil microorganisms tend to get to it first, and swiftly use most of it.

Simply growing clover with other plants does not guarantee they will be ‘naturally fertilised,’ despite the many overly simple, wishful, and fanciful claims that it does.

Nodule leak fertilisation can and does happen, but provides only relatively small amounts of plant available fertiliser, and usually needs an environmental stressor such as defoliation to negatively influences its roots for the nitrogen to be usefully released. It also needs to be on a large lawn or field-sized scale before its effects are sufficient to be measurable. The system can reestablish itself as the plant regrows and be a cyclical process if occasionally mown or repeatedly grazed.

In infrequently mown lawns such as tapestry lawns where roots have time to regenerate, this cycle can be of benefit over time as it helps support diverse microbial life in the soil, and aids in maintaining and improving soil structure for better overall growth. There is a smidgen of additional organically derived nitrogen too.

Tapestry lawns do not need additional fertilising of any kind.

Nutrient cycling within a T-lawn is sufficient. Adding additional fertiliser to a T-lawn acts as a sudden nutrient overdose; it skews growth to those plants that are quick to metabolise free nutrients and usually negatively influences bacterial-plant mutualisms. It should not be undertaken.

An ornamental plant for lawn gardening - sometimes.

White clover has a variety of forms, from large leaved forage types bred especially for animal grazing and therefore unsuitable for a domestic lawn, to the intermediate so called ‘Dutch’ type commonly found in British and continental garden lawns. Small-leaved forms specifically for use in lawns, and termed ‘micro-clovers,’ have also recently become available

Pollinator attracting white clover waits for 14 hours of daylight before flowering fully and produces most of its nectar when temperature reaches the 20°C mark. Once a major part of bee summer diets, its availability has dwindled as its use in clover leys (grass + clover grazing) has dropped substantially over time. Ironically, in some places, it is non-native Himalayan balsam that replaces it in the bee diet. Over 60 invertebrate species, including beetles, bugs, flies, and micro-moths, directly rely on it, in addition to all the visiting bees.

White clover is not the first plant most people would think of as being ornamentally useful. Currently, you do not find them commonly in baskets or borders, however that is glacially changing.

It is a timely and fortuitous, if laboriously slow change to my mind; since if we are to seriously explore all the possibilities and benefits of gardening the lawn, then white clover is a plant to most definitely include in our plant palette.

Firstly, by adding a touch of unexpected colour to flowers in the lawn. The colour of white clover flowers does not have to be consistently white. It can range from a clean white to pinks and through to deep maroon. There is not a royal purple one I know of yet, but I am ever hopeful.

Garden centres can sometimes be found stocking a few red-flowered forms, but these are usually sold primarily on the colouration found on the foliage rather than simply the flowers. In retail, simple green-leaved but red-flowered forms are almost unknown, even though such a form naturally exists and is native to the UK.

A few years ago, when I had the time, opportunity, and resources of a university department to call on, I grew several different forms of white clover, and dabbled in selection and cross-breeding. I was looking at things like leaf-stem length, overall habit, chlorophyll content and leaf area. All the better to understand how this important lawn plant could be used in grass-free lawns.

In the process, I became delighted and intrigued by the surprising variety of leaf patterning and colouration to be found on the plant most of us have in our lawns but never actually planted.

I have some images from then that show some of the interesting and rather attractive ornamental variations that can occur on this currently undervalued plant.

How these colours and patterns show in a typical grassy lawn is variable, but nevertheless interesting. Lawns simply do not have to be just grass!

There is one form I have kept hold of due to its peculiar pigmentation. It has three leaflets as is usual, and a pleasing red feather-like pattern; however, around Easter time the central leaflet turns red as if splashed by drops of blood. It is quite noticeable. The first time I saw it, I thought someone must have had a nosebleed. If I were to be handing out common names, I would probably choose something like 'Easter clover', 'Nose-bleed clover,' or 'Bloody clover,' and not be swearing at all.

A touch of luck is never to be sniffed at, and with lucky clover there is roughly a one in ten thousand chance that a genetic variation will produce a rare fourth leaflet instead of the usual three. You have to be very lucky to find one. A patterned ornamental one is surely even rarer.

For a list of 40 different types of clover, click here.