Species diversity is a term used to define the different number of species in an area (species richness), their abundance (number of individuals) and their distribution. It is a measure of variety in an ecosystem.

Gardens can be viewed as mini-ecosystems, and lawns can be part of that ecosystem. They can be especially valuable parts if they contain lots of different plants rather than just grasses.

Species diversity helps buffer environmental stresses on an ecosystem. A diverse ecosystem has a better chance of surviving rapid changes with minimal losses. Too hot, too cold, too wet, too dry, but something is likely to survive.

Species diversity plays an important role in providing a variety of diets over time for the organisms in the ecosystem. Spring blooms, summer blooms, autumn blooms, a variety of different leaves to munch on, it is plant diversity that leads to a complex food web over time rather than a simple food chain.

Honeybees, wild bees, and hoverflies have been shown to respond positively to increasing flower richness, whereas some insect pollinator groups also respond to the size of the flowering plant area.

Larger planted areas with more diverse flower species have been shown to be more suitable for the conservation of wild pollinators in particular.

T-lawns are scalable. They can be small to large and contain many species and hundreds of thousands of blooms over a year depending on how they are planted and managed.

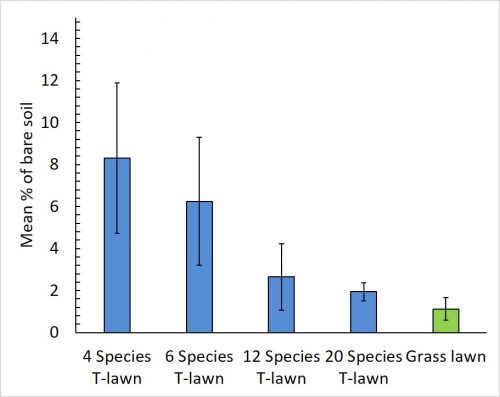

Research indicated that in T-lawns a basic minimum of 12 very different plant species are required for useful ground coverage and a broadly balanced lawn with just enough diversity so that it does not become quickly dominated by the fastest and strongest growing plants.

However, the most successful, robust, and visually appealing T-lawns have closer to 30+ plant forms included in the lawn, sometimes making it appear to be a compact diversity hot spot, in smaller gardens in particular.

For comparison, a rare species rich grassland is one that has 15+ different plants per square metre and 30%+ wildflower cover. T-lawns can match this, usually with greater floral cover and for over a longer period. Perhaps simply a T-lawn garden rather than a traditional border garden might be an option.

Tapestry lawns are created using mostly mowing-tolerant forbs. Forbs are non-woody flowering plants, a grouping that specifically excludes grasses.

Most of the plants used in T-lawns are clonal, they can spread by rhizomes and runners or root easily when in contact with the soil e.g. Trifolium repens (White clover), but not all. Some like Trifolium pratense (Red clover) are not clonal and spread by seed not runners.

Currently, most T-lawn species are British native plants and their cultivars (nativars). However, many near-natives and non-natives can be also be very useful.

In British gardens and parks, the use of non-natives is very common indeed; native-only gardens are rather rare. Britain simply does not have enough native plant species to fulfil the desires gardeners have for their gardens, and our temperate climate allows for many non-natives to be grown here.

The study looking at native-only and mixed-origin T-lawns indicated no significant difference between the two in the number and variety of invertebrates to be found. Both forms supported more life than grass-only lawns. Anecdotally, when asked, most people preferred the look of the mixed-origin lawns, native-only lawns were seen as less interesting.

Non-natives also substantially extend the floral season of the lawn. From mid to late winter when snowdrops and crocus first appear (both non-natives) all the way through to the November-flowering blue pea (Parachetus communis), non-natives add colour and floral resources as well as useful ground cover foliage. They notably extend the season once most British natives have passed their peak flowering period in late spring and early Summer.

Details of over 30 tested T-lawn suitable plants are available in that very reasonably priced book of mine: Tapestry Lawns: Freed from Grass and Full of Flowers.